Wenshan: An Australian company making a difference

16 May 2018

Over Easter, I had the pleasure of visiting Wenshan, a prefecture in Yunnan’s far south, right on the border with Vietnam. Officially known as the Wenshan Zhuang and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, the region of 3.6 million people was celebrating 60 years since its establishment. As one of China’s most diverse prefectures, Wenshan is home to 11 ethnic groups, not just the Zhuang and Miao mentioned in its title. A local saying tries to make sense of this diversity – The Han and Hui live in the towns, the Zhuang and Dai live on the water, the Miao and Dong live in the hills, and the Yao live in the bamboo groves!

Zhuang performers share folk stories, which often take the form of songs

In fact, most of these ethnic groups live in traditional areas that pre-dated the national borders that we observe today. There are related clans that live across the borders of two or more countries. For example, the Zhuang live in Vietnam, Laos and Thailand, as well as in China’s Yunnan, Guizhou and Guangxi provinces. And the Dai people are closely related to Thais, with remarkably similar cultural practices. But diversity within groups is common too, with many branches within an ethnic group having different traditions and linguistic variations. Some ethnographers argue there are far more ethnic groups in the border regions than officially categorised.

At the anniversary celebrations, I came across a large number of colourfully-adorned people identifying themselves as Hmongs who now live in the United States. Failing to draw the connection between Wenshan and the Hmong, I asked them why they were attending the anniversary. Their response revealed a fascinating but complex history of the Hmong, known as the Miao in China. The elders from the group tell me that the Hmong/Miao people have a long history of migration, dating back thousands of years, when their people were united by a mythical king in northern China. Through centuries of war and prosecution, they lost ground, gradually moved southwards, and eventually settled down for several centuries in what is now the Wenshan area.

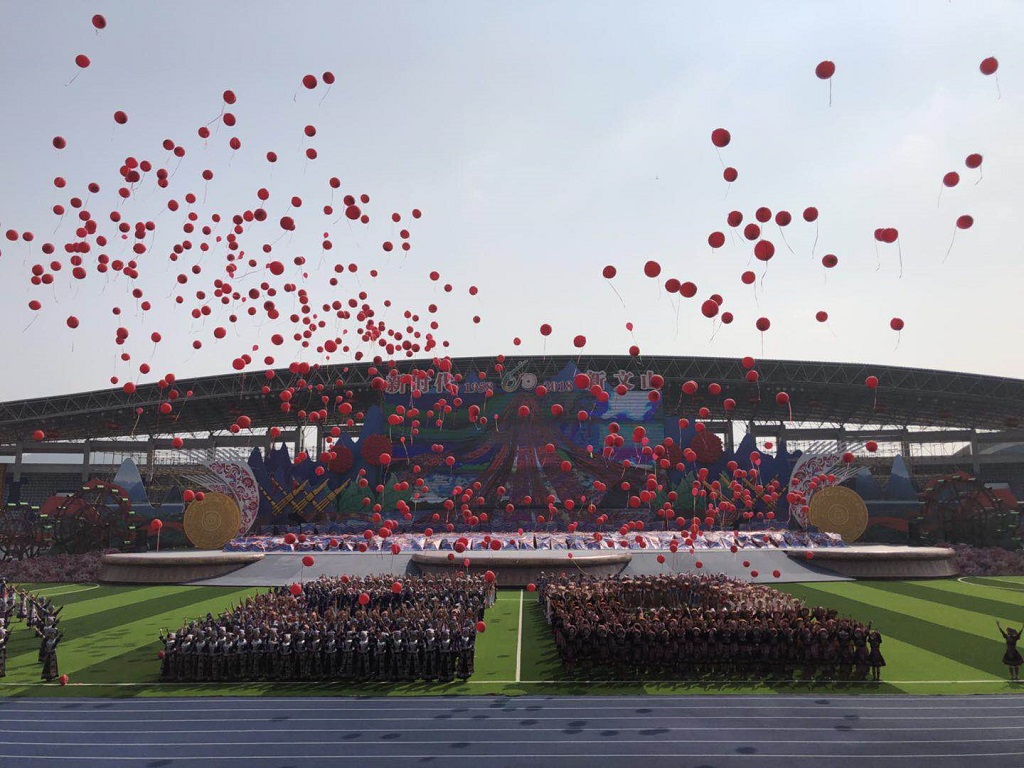

Wenshan celebrates 60 years in style

During the Qing Dynasty, the Hmong/Miao became targets of military campaigns, which killed large numbers. The group scattered to modern day Laos, Vietnam and Thailand, as well as into mountains of China’s southwest. The Chinese civil war in the 1940s led another wave of Hmong/Miao to migrate to mainland Southeast Asia. Tumultuous conflict in Laos and Vietnam in the 1970s then resulted in waves of Hmong seeking refuge around the world, including to Australia, where an estimated 2,000 Hmongs have been resettled.

So representatives of the Hmong diaspora came to Wenshan to recognise it as their ancestral home in their epic millennia-long journey. It was quite moving and a testament to their resilience and adaptability.

Neolithic ‘Great King’ paintings in Malipo, Wenshan. Credit: Wikimedia Commons user Pratyeka

But the main reason I came to Wenshan was to visit an extraordinary project started by a Chinese-Australian scientist, Dr Ken Yang, that integrates biotechnological research, eco-tourism and sustainable agriculture.

Meet Dr Ken Yang

Dr Yang’s organic fertiliser company, Aust-for, has invested $125 million into the Sino-Australian Centre for Research and Development of Sustainable Biological Resources. Known as the Sino-Australian Eco-Park in short, the centre covers 100 hectares and is primarily a research and demonstration facility focused on developing innovative and sustainable agricultural production. It has a special emphasis on the “soil to table” food concept, as well as using local and Australian expertise and products. The centre’s eco-tourism facilities are open to the public. Eventually, it will also have a marketplace that will sell organically grown vegetables, and a restaurant serving healthy sustainable food.

Consul-General Christopher Lim gives an address at the opening ceremony

A member of the Zhuang ethnic group, Dr Yang hails from the Wenshan region. He found success as a young man by establishing a logistics and agriculture company in Shandong province. Dr Yang then undertook further studies and research in agriculture in Australia, before settling in Brisbane. Locally, he is well known as a leader in the Chinese migrant community promoting multiculturalism and understanding.

Keen to strengthen Australia’s links with his home region, Dr Yang found a site in Yanshan county to realise his vision of building an agricultural research centre that would encourage ecological sustainability, find new ways of improving agricultural yields and helping to develop the impoverished region.

Showcasing Australian expertise in sustainable horticulture

Yanshan is one of China’s poorest counties. But change is taking place at a rapid rate in the larger prefecture. This year, the establishment of a high speed rail link to Kunming has reduced the previous five-hour road trip to one hour. This, and other efforts to develop the region, have led Wenshan to become an important supplier to the Chinese market of traditional Chinese medicines, particularly a type of ginseng called sanqi (三七) or notoginseng, as well as vegetables and chillies.

I was delighted to visit the centre as the Australian Consulate-General has been supporting the project since its inception. My predecessor, Nancy Gordon, officially opened the centre in 2015 with the Yanshan Party Secretary Li Hong, whom I met when I visited last month. I was struck by her commitment to the project and the detailed knowledge she had about the centre’s development. Dr Yang told me having close links with the local government had been important in obtaining the necessary approvals, incentives and assistance, particularly when the project was unprecedented in scale, concept and innovation, in this remote region. It required considerable discussions, trust and cooperation to bring the project to completion. Austrade’s Kunming office also facilitated key meetings and visits with local government departments on land use, regulations for imported products, and project scope. This helped contribute to the project’s success.

I learnt that the centre has found an innovative method of using the waste products of coal mining and mushroom cultivation to make organic and non-polluting fertiliser that stimulates plants’ natural ability to grow robustly. The centre also researches how to grow notoginseng in a sustainable manner that leaves the soil in a healthy state. The centre’s emphasis on low impact development is impressive. It has a sophisticated rainwater collection and purification system that means the park doesn’t use water from the mains. Similarly, the centre doesn’t use electricity from the grid as it uses solar panels to generate power to support fertiliser production.

Two Sunshine Coast organisations, Centre for Growing Sustainability and Global Boss, provided technical, consulting and organic farming products to the centre’s vegetable, lavender and edible rose farms. Both plan to expand their exports to China using the centre as a demonstration base.

Energy-smart cultivation is improving agricultural yields

I came away from the Sino-Australian Eco-Park with a strong sense of pride. Owing to the commitment of a Chinese Australian to developing links between his new home and the place where he was born, there now exists a fully functioning research farm and place to learn and enjoy the natural environment. It shows that an individual, even from the most remote part of the world, can make a difference.

Click here to return to Australian Consul-General's Blog on Southwest China