How to handle a formal meeting in China

25 October 2018

Early in my career, I had the privilege of attending several formal meetings in China as a note-taker. Hosted by the Chinese side and involving visiting Australian Ministers, Parliamentarians or senior officials, these meetings have a formality that makes them very different from what we’re used to in Australia.

Meetings in China have a higher level of formality than is common in Australia

The meetings are similar to what you see on TV, where Chinese state leaders meet foreign dignitaries in grand and imposing settings. To many of us, such interactions look scripted and theatrical.

Most Australians tend to prefer business meetings to be informal, frank and involving just a few decision-makers. We’re familiar with being seated in a lounge suite in someone’s office or a conference room. We may even meet in a café or pub. We often get straight to the point, stating the reason for the meeting upfront, and giving supporting evidence through the discussion with the view to persuade the other party. If things go according to plan, we can expect follow-up and continued contact through emails.

Formal meetings in China, however, conducted in Chinese and with a high degree of formality and ritual, are very different and can be overwhelming. I certainly felt so early in my career. Through experience and a lot of practice, however, I learnt that there are certain expected behaviours. Let me share some of the unwritten rules as I understand them so that you can be better prepared. In this blog, I’m assuming that the fictional Chinese host is at a similar level of seniority to you.

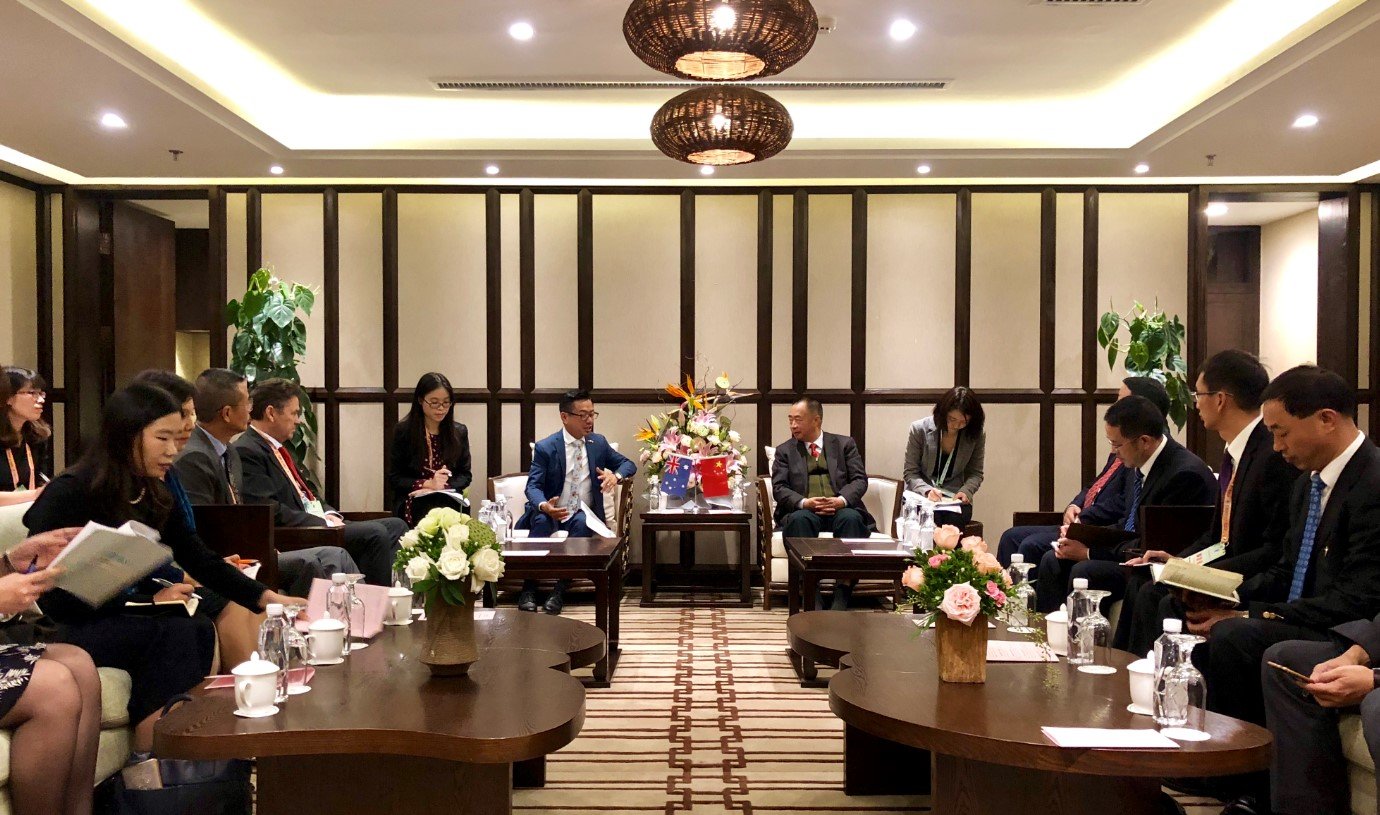

Gold Coast Mayor Tom Tate meets Chengdu Mayor Luo Qiang

As formal meetings normally involve senior local officials or the leadership of companies, whether private or state-owned, they are key to establishing relationships and are an opportunity for you to present your jurisdiction or company’s capabilities. It’s important to make the most of your time with these leaders, who are often difficult to access.

What to expect

Meetings mostly come in two seating formats – boardroom-table style or horse-shoe style. The latter is the more challenging but boardroom-table style meetings may be just as awkward. Proper meetings rarely take place around a lounge suite.

In addition to cultural and language differences, what makes Chinese meetings challenging for us is a particular style and format that we’re simply not used to.

Consul-General Christopher Lim in discussion with Sichuan Foreign and Overseas Chinese Affairs Office Director-General Zheng Li

There is a clear distinction between which party is the host and which the guest. For the more formal horseshoe-format meeting, you and your delegation are expected to enter the meeting room when the host is ready to greet you. To ensure that the timing is aligned, you’ll often be placed in a holding room before entering the meeting room proper.

In regard to dress code, I have discovered that the term ‘business attire’ can mean different things to different people. It’s best to check what the Chinese side expects, for example, whether it means a jacket with a tie for men. Depending on the weather, seniority and setting, the attire at a meeting can vary. Be ready to take it in your stride if your Chinese counterparts don’t follow the dress code that we’re used to.

Entering the meeting room

You and your delegation then walk into the meeting room in protocol or seniority order, shaking hands and exchanging business cards with the host and their delegates one by one before proceeding to your allocated seats. Your entrance and greeting by the host is a key part of the ritual, hence the moment is almost always photographed.

The Chinese side will expect the leader of your delegation to do most of the talking. If your delegation doesn’t have a clear leader, it may be uncomfortable for the Chinese side, who may not know where to focus their attention. In this event, it’s best to nominate someone to take the leadership role and let the Chinese side know before the event.

Look first for your nameplate before taking a seat in a horse-shoe style meeting room

Nameplates are normally provided to indicate where everyone sits. In the absence of nameplates, your host is expected to point you to where you should sit. There are usually a larger number of participants on the Chinese side who wait for the proceedings to start. Their roles are often not immediately obvious. If the arrangement is a horseshoe-style, large chairs are used, which are usually placed far apart from each other. To many this makes the occasion feel stiff and formal. Don’t be surprised if there are microphones especially if the room is particularly big. Practise using a microphone ensures your amplified voice isn’t either too loud or too soft.

Depending on whom you’re meeting, it isn’t out of the question for local television crews to record a fair portion – if not all – of the proceedings. You could check beforehand what your Chinese counterparts are planning, and agree in advance on when the media should leave the meeting.

The welcome, introduction and overview

The Chinese host will start the meeting by welcoming you in very warm and generous language, perhaps even to the point of embarrassment. According to my understanding, this is considered polite and indicates they are treating you with respect. But don’t let it go to your head!

Then, the host will introduce you to the delegates on their side, all done while everyone is seated. You may wish to acknowledge each one of them by nodding.

All this will be interpreted consecutively, usually by professional interpreters or members of each delegation, who sit just behind or to the side of the leading speakers. The quality of interpreters can vary, however. I make sure that my own side has a highly capable interpreter (even if I conduct the meeting in Chinese) who can take notes and make sure we don’t miss any cultural, technical or linguistic nuances.

An interpreter stands by to assist Victoria’s Minister for Trade and Investment Philip Dalidakis

You’ll see that the host will pause after a few sentences for the interpreter to translate into English. This is a particular art that is important to do well so as to convey the full impact of what you say.

The host will often begin their remarks by providing an overview of their city, region or company. There may be a prepared statement that the host will read, or may just sound like it. These overviews come with a few familiar components – location, origins and statistics. For example, the host may say “Sichuan has a permanent resident population of 90 million and a GDP of 3.69 trillion RMB, ranking sixth in China”, “Chongqing municipality, located on the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, is an important meeting point of the Belt and Road Initiative and the Yangtze River Economic Belt” or “The China Southwest Architecture Design and Research Institute was established in 1950”.

The logic of this approach is to start with the overall picture and then focus on the specific. In the Chinese framework, this narrative provides context to the projects or issues you’ll discuss and gives them gravitas. The overview might take a while, especially when interpreted. The trick is to listen politely, and take mental (or physical) note of what the host says that you could refer to when it’s your turn to speak.

Go with the flow

The host will eventually refer to you, your city or your company. They might say how impressed they are by your entity’s achievements and how cooperating could benefit both parties. They would have had prior briefing, so in many cases, the meeting is an opportunity for the senior leader to hear from you and set out the basis for future cooperation.

Then comes the crucial part of the discussion, the host will finally set out their expectations for moving forward. I’ve seen this come in the form of the host putting forward “three suggestions”. At times, the suggestions may not sound like much, such as “proposing to enhance exchanges”, “agreeing to deepen understanding between the two sides”. However, there could be a logical sequence to these steps, which may lead to opening the way for substantive collaboration down the road.

Down to business

Hence, it is important to go with the flow. I’ve learnt that what may sound like a monologue to me and appears to take up valuable time may actually be part of a genuine process to establish confidence.

You may hear your host praising your role in the bilateral relationship between Australia and China. This is a polite way of acknowledging that you’ve made an effort to come all the way from Australia to seek cooperation with the city, prefecture or company. It also puts your project in the context of the development of the bilateral relationship. In the Chinese frame of reference, context is important and one’s actions should be consistent with an overall global trend or the trajectory of a bilateral relationship. It would be difficult for projects to operate in a vacuum, or run against the grain of political developments.

Finally, it’s your turn

It’s your turn to speak once the host draws their introduction to a conclusion by welcoming you again. It would be unusual for you to interrupt before their conclusion. This may throw the well-established sequence of the meeting off balance.

Following the normal pattern of Chinese meetings, you could begin by expressing your delight at being in the particular city, meeting the senior leader, and warm reception accorded to you, and introduce your own delegation. Don’t forget to pause for interpretation. Entering the discussion with an overarching macro-level topic – especially where there is a common interest – would go down well. For example, depending on what might be relevant to your pitch, you could start with the multifaceted and mutually beneficial bilateral relationship between Australia and China, the growing importance of innovation globally, or the need for more effective environmental management.

Consul-General Lim in discussion with Lincang Mayor Zhang Zhizheng at a meeting held during the 2018 International Macadamia Symposium

You could refer to the host’s earlier description of what your city or company has to offer and provide background information. Using the Chinese style of referencing location, origins and statistics (as mentioned above) would resonate well with the host.

After setting all this up, you’re in a good position to put forward what you’d like to get out of the meeting. Working the host’s earlier suggestions into the discussion could be useful. Apart from anything else, it shows that you’ve been listening carefully.

While the Chinese side expects that there would be one leader on your side, it doesn’t mean that other members of your delegation can’t speak. You can ask a member of your delegation contribute to the discussion by introducing them at an appropriate time.

Finally, you can conclude by using further pleasantries and underlining your commitment to working together.

Further exchange

The host will respond to your points, probably with some generosity. If this was your first meeting, an outright commitment to work together is rare. Like us, the Chinese side is likely to require internal consultations. This is normal.

An exchange of gifts between Mayor Tom Tate and Mayor Luo Qiang

There may be an opportunity for you to say more if the host doesn’t draw the meeting to a conclusion. If you still have something else important to state, it should be done concisely.

A typical way a host concludes a meeting is by summing up. It could be in the form of “both sides reaching a consensus” on certain topics, or an expressed hope to cooperate, for example. Sometimes, the host may provide you with a point of contact for follow-up. You could respond by appointing a person on your side. If a banquet follows, the host might say that you could carry on the discussions during dinner.

A group photograph is common after a meeting has concluded

Finally, there’s the possibility of a gift exchange. While Australia doesn’t have a gift-giving culture, it is common in China, especially when meeting potential business partners or senior government officials for the first time. Often the host will present a gift that reflects traditional or local culture. If you think it is impolite to decline, you should accept the gift. You should also reciprocate with a gift unique to your region.

In my experience, it is in your interest to follow up on a meeting. You could do this through an exchange of letters or further visits by yourself or team members. Best of all, you could invite your host to visit your city or company in Australia. (In a future blog, I’ll set out what I think what you, as a host, could do to ensure Chinese guests have a good visit in Australia.)

Of course, the above is my own personal experience of handling formal meetings in China. You don’t have to follow the pattern set by your Chinese host. But what I’ve realised over the years is that understanding how my interlocutors operate and getting in sync with them actually helps with building trust and confidence. This in turns puts me in the best position to achieve Australia’s goals in China.

Click here to return to Australian Consul-General's Blog on Southwest China