Sojourners in the southwest: Quarantine readings (Part 1)

18 June 2020

Like many of you, I did a fair bit of reading and contemplation during the coronavirus lockdown. I rediscovered books I read years ago, viewed them with more experienced eyes, and uncovered new insights.

Only a few books are about southwest China. This region hasn’t received much attention in the myriad of books written about China. Let me share with you the books about this rich and colourful region that have had an impact on me.

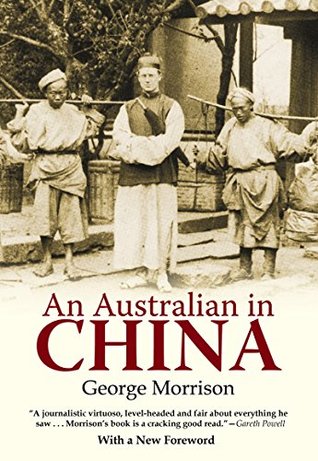

Here is the first of two blogs about these books. They are classics in their own right – the extraordinary travelogue An Australian in China by George Morrison and the evocative fiction Lost Horizon by James Hilton.

An Australian in China by George E Morrison, originally published 1895

For me, this is an incredible book about China because it was written by a remarkable Australian well before we became a nation state. Born in Geelong in 1862, George Earnest Morrison became a physician, adventurer, foreign correspondent, and even a political adviser to the Chinese Government. Australian sinologist Andrew Chubb noted in the foreword of the 2009 edition of the book that Morrison was one of the most extraordinary Australians who ever lived.

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920) as a young man. Credit: The Morrison collection, State Library of NSW

An Australian in China chronicled Morrison’s journey from Shanghai to Rangoon in 1894. Chubb described the journey as “one of the great Old China adventures: up the Yangtze rapids in a tiny wuban, or “five-planter” boat to Chongqing, over stony paths across the wilds of Sichuan and Yunnan, through the Shan states to British-ruled Burma”.

Morrison’s Chinese passport (Photo from An Australian in China)

Amazingly Morrison spoke no Chinese, had no interpreter or companion, and was unarmed.

Rather than detailing the difficulties of such an epic journey, Morrison did the exact opposite.

Morrison with some local helpers in western China. (Photo from An Australian in China)

“The ensuing narrative will tell how easily pleasantly this journey, which a few years ago would have been regarded as a formidable undertaking, can now be done.”

I am particularly fascinated by Morrison’s descriptions of the places I have been to on my travels in southwest China – Chongqing (“an open port”, “an enormously rich city”), Luzhou (“one of the richest and most populous in the upper Yangtze”), Yibin (“immensely rich”, with a number of churches, temples and mosques, as well as opium houses), Kunming (“one of the great cities of China” because of its strategic location between French Indochina and British-ruled Burma, and “the great gold emporium of China”, supposedly visited by Marco Polo), and Dali (“always been an important city”, as capital of the Nanzhou (738-937) and Dali Kingdoms (937-1253), and the headquarters of the Panthay Rebellion (1856-73) under Muslim leader Du Wenxiu.

A suspension bridge in far western China. (Photo from An Australian in China)

He described Sichuan as “by far the richest province of the 18 that constitute the Middle Kingdom”, and a “Catholic stronghold”, with “100,000 Catholics in the province, representing the labours of many French missionaries … of more than 200 years”.

I’m surprised to learn that Morrison got by with money transfers through banks which telegraphed the money along his journey. “Money is … remitted in Western China with complete confidence and security”, Morrison said. This was 1894!

Snow-clad mountains behind Dali. (Photo from An Australian in China)

Morrison described his local travel companions and the inhabitants of the various places he visited, as full of good humour, cheerful, untiring and pleasant. These descriptions remain accurate to this day.

View of Yunnan City, now called Kunming. (Photo from An Australian in China)

The most important part of this book for me is Morrison’s perspective – this was the first comprehensive account of our region through Australian eyes, rather than through a British prism (Australia was still a collection of British colonies at that time.) Eiko Woodhouse argued in The Chinese Hsinhai Revolution that Morrison’s subsequent foray into great power diplomacy in Beijing during the Xinhai Revolution shows that his primary concern was for Australia’s interests in our region. As such, Morrison was a critical part of the growing Australian consciousness about our place in the Indo-Pacific region.

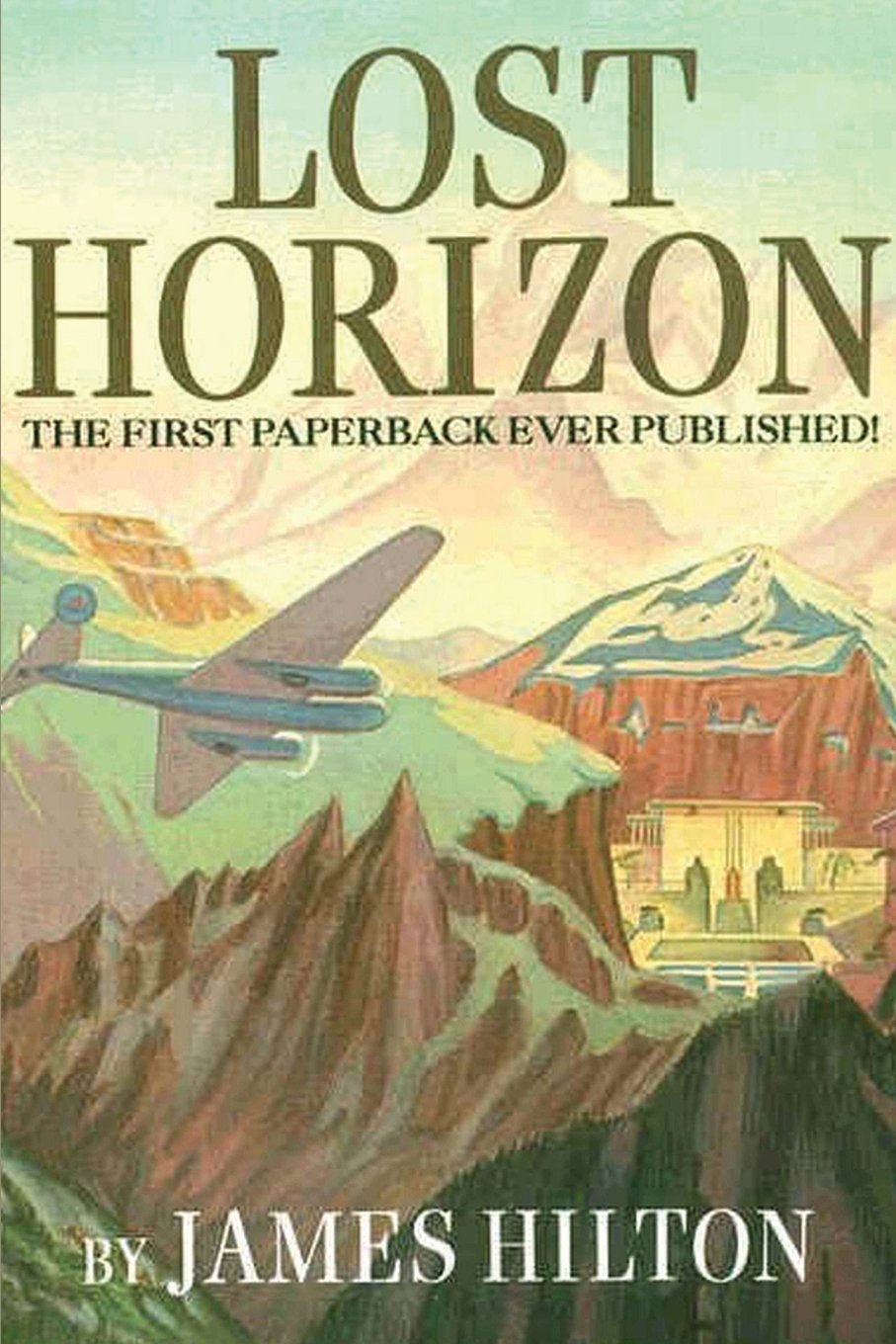

Lost Horizon by James Hilton, originally published 1933

This book created the myth of Shangri-la and shaped Western ideas of Tibetan civilisation for generations. It was written in an age of considerable fascination of alternative societies, when movies and books such as Metropolis (1927) and Animal Farm (1945) were popular.

Lost Horizon starts dramatically with a group of people escaping civil unrest in Baskul, Persia by plane in 1931. But the plane ran out of fuel and had a bad landing in the Himalayas, killing the pilot and leaving the passengers stranded.

Shuangqiao Valley, Mount Siguniang Park in Sichuan. Credit: DFAT

The protagonists in this story were British Consul Hugh Conway, his younger colleague Vice-Consul Charles Mallinson, Christian missionary Roberta Brinklow, and Henry Barnard, an American man with a shady past.

They were rescued by locals who brought them to a small lamasery called Shangri-la, hidden in a beautiful valley where people had lived in an age-defying state for the past 300 years.

Lieren Peak of Shuangqiao Valley, Mount Siguniang in Sichuan. Credit: DFAT

The passengers decided to stay in the lamasery until they were rescued. Conway was spell-bound by the beauty, culture and sophistication of the place and its people. It was paradise. Shangri-la had music, books, art and scriptures. It had no government and no police. Order relied on good manners and moderation.

Barnard was content to be fed well and looked after. Brinklow thought it God’s calling to be sent there to convert the locals to Christianity. But Mallinson wanted to leave as soon as he could. He hated the lamasery, believing it was a prison, an evil place. He didn’t believe in the claims of delayed aging.

Chonggu Temple, Daocheng Yading National Nature Reserve in Sichuan. Credit: DFAT

They met a Chinese girl named Lo-Tsen who played the harpsichord and was waiting to be a lama. Conway fell in love with her. Mallinson later also professed his love for Lo-Tsen.

But Mallinson’s impatience to leave soon became overwhelming. Too scared to leave by himself, he convinced Conway to accompany him and Lo-Tsen to the outside world.

Conway had been told by the locals that Lo-Tsen was an 18 year old Manchu princess who was traveling in the mountains for her wedding over a century ago and got lost only to end up in Shangri-la. If she left Shangri-la, the ageing process would catch up with her and she would die. Mallinson said the story wasn’t based on fact.

Torn between staying in his utopia and his loyalty to Mallinson, Conway eventually chose to help his friend. Barnard and Brinklow decided to stay in Shangri-la.

Chonggu Temple, Daocheng Yading National Nature Reserve in Sichuan. Credit: DFAT

Conway, Mallinson and Lo-Tsen eventually made their way out of the valley but not before an avalanche claimed Mallinson’s life.

Conway survived but lost his memory. He was later reported to be brought in to a hospital in Chongqing by a very old Chinese woman who then died.

When Conway recovered his memory, his longing for Shangri-la compelled him to make the hazardous trek back to the paradise he loved. But did he make it?

Click here to return to the Australian Consul-General's Blog on Southwest China