Sojourners in the southwest: Quarantine readings (Part 2)

24 June 2020

This is the second of two blogs about my favourite books about southwest China. The three books I’ll feature are all non-fiction pieces. River Town and Shark Fin and Sichuan Pepper are accessible and delightful reading. The Sichuan Frontier and Tibet: Imperial Strategy in the Early Qing is more academically focused but is essential reading for those with a deep interest in southwest China or the Qing Dynasty.

River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze by Peter Hessler, 2001

This New York Times bestseller lives up to its reputation as a mesmerising, insightful, and poignant account of a young American’s experience in a remote part of southwest China in the 1990s.

River Town is beautifully written by Peter Hessler. As a US Peace Corps volunteer, he was sent to teach in a teacher’s college in Fuling, a misty town at the junction of the Wu and Yangtze rivers, then in Sichuan province. The nearest major city – Chongqing – was an eight-hour boat ride away.

Hessler weaves a series of personal and intimate stories of his students, who were training to become English teachers in Chinese secondary schools, and his discovery of a rapidly changing China, then exemplified by the construction of the world’s largest dam, the Three Gorges Dam, just downstream.

Peter Hessler and his family with the Australian Consulate General team. Credit: DFAT

The book resonated with me deeply because so many of his stories, feelings and impressions had a familiar ring to my own China journey. While my experience was vastly different from his – I was learning Mandarin full time and then working as a diplomat in Shanghai and Beijing respectively and am of Asian descent – but there were similar lessons and echoes to our respective journeys of discovery and appreciation of China.

I like this excerpt of Hessler talking to Anne, one of his Chinese students. It is acutely observed, and I also remember that period in 1997.

“Have you heard what happened” she asked

“Here in the college?”

“No, in Beijing,” she said. “Deng Xiaoping is dead.”

I said I was sorry, and I asked when he had passed away.

“Yesterday. They told us on the television today before noon. When I heard, I felt like crying.”

She smiled as she spoke, but it was the Chinese smile that served as a mask against deeper feelings. Those smiles could hide many emotions – embarrassment, anger, sadness. When the people smiled like that, it was as if all of the emotion was wound tightly and displaced; sometimes you caught a glimpse of it in the eyes, or at the corner of a mouth, or perhaps a single wrinkle stretching sadly across a forehead. Anne had high cheekbones and deep dimples, and today I thought I saw a trace of her sadness wavering along her cheek.

The Sichuan Frontier and Tibet: Imperial Strategy in the Early Qing by Yingcong Dai, 2009

For a DFAT officer who is posted to Chengdu, this book is essential reading. Primarily about the Qing Dynasty’s policies towards Sichuan and the Tibetan regions from the latter half of the 17th century, this book meticulously sets out the geopolitical importance the Qing emperors attached to the region at the time.

Throughout history, imperial strategy towards Sichuan varied. During the Tang and Song Dynasties, the Sichuan region had been a key economic area, making significant contributions to the empire comparable to those of eastern China. This was the time when the world’s first paper currency was invented as a promissory note in Chengdu – the jiaozi. There was a saying yangyi yier (扬一益二 translated as Chengdu is only second to Yangzhou (Jiangnan/eastern China) in its wealth)

But Sichuan lost this status after the devastating Mongol conquest in the 13th century, as its economic weight slipped. Sichuan was almost annihilated during the Ming-Qing transition, owing to rebellion and famine.

Although the Qing annexed Sichuan, its laissez-faire policy had left the area mostly autonomous. Local chieftains and Buddhist monasteries remained in power in their chieftaincies.

The book argues that at the end of the 17th century, the Qing realised that the Tibetan Buddhist establishment was instrumental in pacifying various Mongol tribes, so was propelled to focus on its policy towards Tibet. Central to this policy was Sichuan, the adjacent province that was the key strategic approach to the Tibetan areas.

Thus began the Qing’s generous preferential policies towards Sichuan, designed to strengthen its economic capability and enhance its strategic importance, for the Qing’s interests in Tibet.

I recommend this book to budding Chinese scholars interested in the historic underpinnings of the southwestern part of China, a region critical in empire building involving the Han, Tibetans, Mongols and Manchus.

Sichuan is the most important province in the western territory of the country, with difficult topography and wealthy residents. It has always been deemed critical in the security of the country… If Sichuan is lost, then Yunnan, Guizhou and Guangxi could no longer expect any military funds, Hubei and Hunan could no longer collect lijin on commodities from and to Sichuan, and Shaanxi and Henan would also be in a dangerous position and exposed to [rebels’] attack.

Luo Bingzhang, Governor of Hunan, 1860

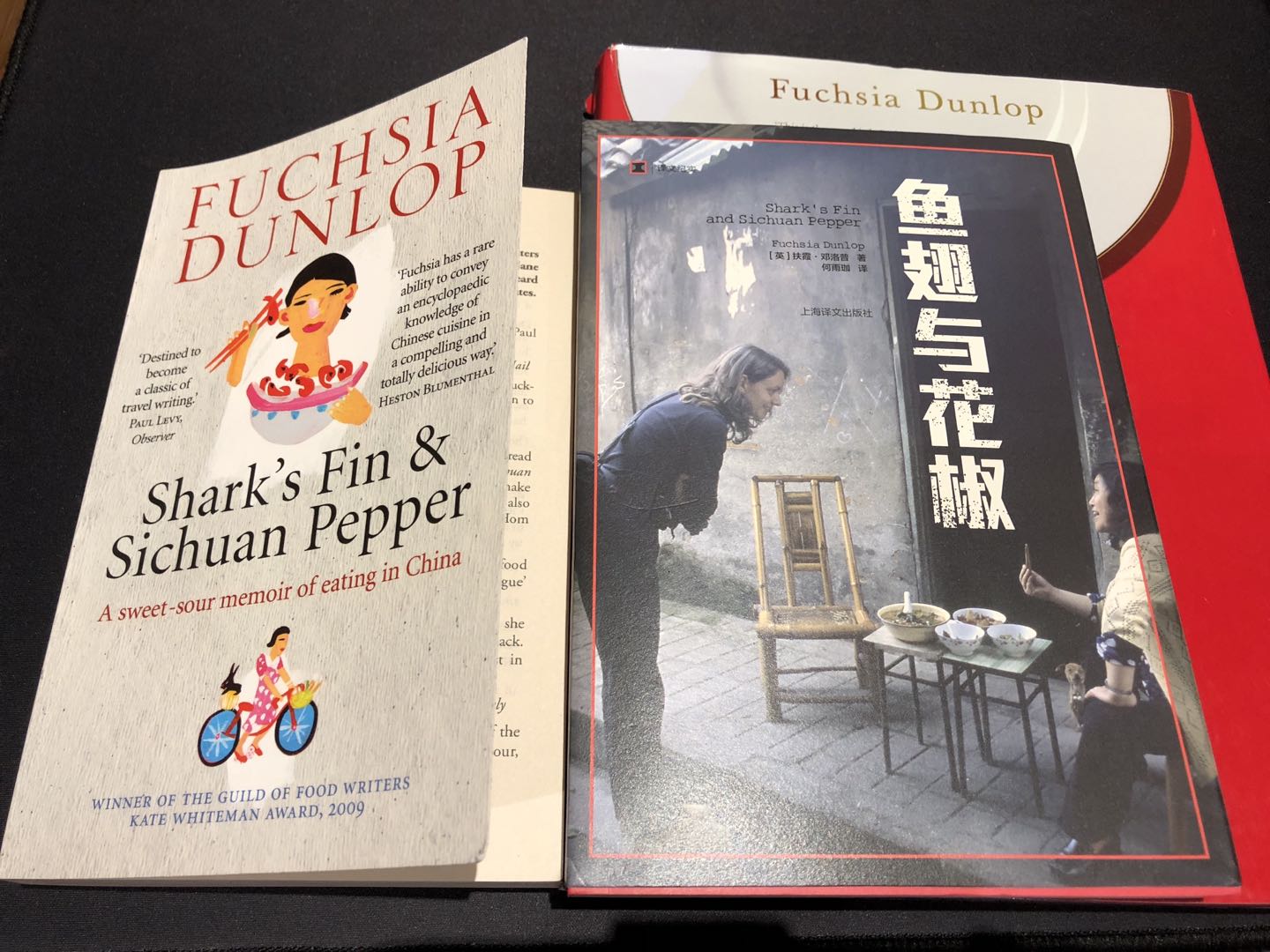

Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A sweet-sour memoir of eating in China by Fuchsia Dunlop, 2008

Readers will know I’ve written a fair bit about Sichuan cuisine. If there’s one book to read about the extraordinary food of this province, it has to be Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper by Fuchsia Dunlop. This is the most engaging book about food I’ve ever read. Moreover, it was Dunlop who introduced and explained Sichuan food to the mainstream international audience. Her book is filled with loving and knowledgeable detail of Sichuan cuisine – the cooking, the eating and the history.

I was delighted to have Fuchsia over for a Sichuan meal. Credit: DFAT

In 1994, Dunlop studied Chinese at Sichuan University in Chengdu, she chose the city because of the food. Then she started taking private classes at the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine before becoming the first foreigner to be enrolled in a professional training course full time.

Dunlop has the ability to explain and interpret Sichuan cooking (as well as the other cuisines she writes about) to an international audience that enables us to understand and appreciate it. Take for example, how she explains the concept of kougan (口感), ie, texture or mouth sensation, for which we tend to have limited vocabulary such as crispy, tender and chewy. She has a whole chapter The Rubber Factor to explain what kougan is all about and expands our experience. She writes about the cui (脆) of fresh crunchy vegetables, the tanxing (弹性) of squid balls (bouncy elasticity), the nen (嫩) tenderness of freshly-cooked fish, or hua (滑) the smooth slipperiness of velveted slices of chicken.

Chicken ‘Tofu’ Soup (Ji Dou Hua). Credit: DFAT

Hence, it’s understandable why the Chinese find interest in highly textured food such as sea cucumber, chicken feet, duck’s tongue, goose intestines, ox throat cartilage, abalone, tofu, or even pig aorta. On the widely held simplistic view that the Chinese had to eat offal because of past experience of famine, Dunlop explains to us that there are different explanations as well. There has always been a sophisticated and refined appreciation of food among the elite, found through historical writings. Confucius, for example, was found fussing over whether he was given the correct sauce for his meat. Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu waxed lyrical about the river fish of Sichuan.

Jessie’s Pork with Mashed Garlic and Red Chili Oil is a favourite at our Consulate’s pot luck lunches. Credit: DFAT

I’m happy to clarify there are no shark fin recipes in the book.

Sojourners

I realise the books I selected are all about journeys, from the 19th Century to the present. This is why they reverberated with me. The stories of discovery – whether be it through travel, new tastes, the search for utopia, or new frontiers – are as exciting as they are inspiring.

Click here to return to the Australian Consul-General's Blog on Southwest China