Discovering another migrant society: Sichuan

29 November 2019

Like many migrants in Australia, I am often asked about my origins. I have a prepared personal migration story which I tell with pride: my experience in Australia has been one of overwhelming achievement, success and happiness.

When I first arrived in Chengdu, I imagined I would be asked a lot about my ethnic background. Interestingly, this wasn’t the case.

Guangdong Guild Hall in Chengdu. Credit: DFAT

Initially I thought people were too polite or just assumed I was from China. Later I came to understand that Sichuan and Chongqing are at the heart of a rich and dynamic migrant society that has shaped the culture and attitudes of people here. As migrants are the norm, my story is easy to understand.

Migration to Sichuan in the late 17th and 18th Centuries was one of the major population movements in Chinese history. It was conducted in response to the dramatic decline in the province’s population during changeover from the Ming to the Qing dynasties (ie, from 1644 and the decades that followed).

Shaanxi Guild Hall in Zigong, Sichuan. Credit: DFAT

Calamity and destruction

When Ming rule ended, the transition in southwest China was tumultuous and devastating, exacerbated by famines and epidemics. To make matters worse, a peasant revolt under the leadership of Zhang Xianzhong, the Yellow Tiger, conquered Chongqing and Chengdu in 1644. Zhang’s rule was brief. Qing Dynasty forces moved into the region and killed him in 1647. But before Zhang died, he reportedly unleashed a reign of terror, ordered massacres, and launched a scorched earth campaign across Sichuan. The once fertile “Land of Abundance” became a deserted wasteland, where tigers were fabled to roam villages foraging for human remains, and people allegedly resorted to cannibalism. Refugees fled to neighbouring provinces.

Guangdong Guild Hall in Chengdu. Credit: DFAT

Sichuan’s population fell as much as 90 percent, according to some estimates. In a survey conducted by the Qing in 1661, there were only 16,096 adult males registered in Sichuan. Subsequent uprisings and internal strife exacerbated the province’s devastation.

Give me your poor

To restore Sichuan as one of the empire’s food bowls, and alleviate population pressures elsewhere, the Qing central authorities initiated a series of policies encouraging migration into Sichuan. Incentives such as free plots of land, oxen and seed, lower or no taxes, and even official positions for leaders who brought large numbers of settlers, were enacted.

“ … for the jobless poor who trekked through long distance and came, it is because Sichuan province has vast land and abundant food that they came to seek a livelihood” Qianlong Emperor 1767, in a letter to Aertai, Governor-General of Sichuan

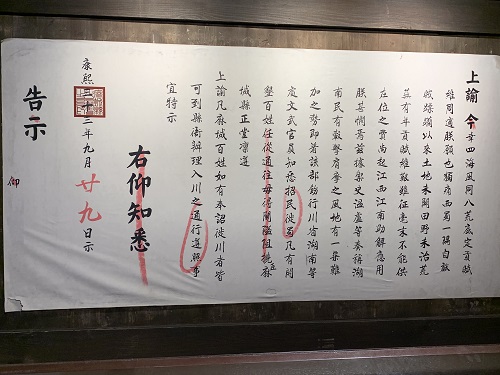

A reproduction of Qing Dynasty Emperor Kangxi's Imperial Edict ordering migration. Credit: DFAT

This enormous movement became known as Huguang tian Sichuan (湖广填四川, ie, Huguang filling Sichuan). Huguang roughly encompassed today’s provinces of Hubei, Hunan, Guangxi, and parts of Guangdong and Guizhou. People from other provinces were also part of the movement. The influx was greatest from 1671 to 1776.

There were essentially three types of migrants – farmers enticed by free land (they accounted for more than half of the movement), those posted or compelled by authorities to settle in the province, and those who, having escaped natural disasters or run from the law, sought a new life.

Qiu Jia Ci Tang (the Qiu family's hall) in Chengdu. Credit: DFAT

Interestingly, among the people who moved to Sichuan in 1671 was the ancestor of the architect of China’s reform and opening, Deng Xiaoping. The Deng family moved from Guangdong in response to the call to repopulate Sichuan.

A new beginning

This influx reinvigorated Sichuan, brought the fertile land back to cultivation, and eventually returned it to prosperity. By the 1720s the province appears to have reached late Ming population levels. During the reigns of Emperors Kangxi (1662-1722) and Qianlong (1736-1795), many business migrants operated shops and factories across Sichuan, fueling economic activity and driving trade. Chongqing, a traditional river trading port, had “thousands of households and many merchants from Jiangsu, Hubei, Fujian, Guangdong, Yunnan, Guizhou, Shaanxi and Henan, who gathered like ants”.

Shaanxi Guild Hall in Zigong, Sichuan. Credit: DFAT

Large-scale immigration continued through the 18th Century, even though unoccupied arable land became increasingly scarce and the population became less able to absorb newcomers. Local authorities began to limit incentives offered to new settlers. But they still came, as migrants were captivated by the myth of boundless opportunity and new beginnings in Sichuan. Soon the province began to feel the pressure of China’s population explosion during that century.

The legacy of Huguang tian Sichuan migration was the rejuvenation of Sichuan as an economic powerhouse in China’s west during the Qing Dynasty. A strong Sichuan base was instrumental to the Qing defeat of the Jinchuan tribes during a series of campaigns in western Sichuan (1747-49 and 1771-76), helping securing the empire’s frontiers.

Qiu Jia Ci Tang (the Qiu family's hall) in Chengdu. Credit: DFAT

In the following decades and centuries, Sichuan’s strong economic foundation was fundamental to its use as a base for the Chinese government in exile during the Second World War, not least because of the key foodstuffs and resources it contributed to the war effort. Since the formation of the People’s Republic of China, Sichuan’s role as the food basket of the country strengthened further, putting the province in a good position to take advantage of the Western Development Strategy from the 2000s to become a modern, thriving economy.

Where did your ancestors come from?

Just as it is important to understand that Australia is a migrant society with long Indigenous settlement, it is useful for Australian businesses, students and tourists coming to Chengdu or Chongqing to know that nearly all of the locals are descendants of an incredible internal migration around 200 to 300 years ago.

Huguang Guild Hall in Chongqing. Credit: DFAT

As Australians know well, a migrant society has its own character and world view, based on the experience of displacement, relocation, adaptation to new and difficult environments, and the building of new communities. In this regard, Australia and Sichuan share a common history, helping bring people together to form rich, vibrant and cohesive societies.

So if the question of my ethnic origins ever comes up in a conversation in Sichuan, I revel in the exchange. It is bound to reveal that we have much in common in our parallel migration stories.

Chongqing’s restored Huguang Guild Hall was a complex of buildings used as a cultural, business and social centre for people from Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi and Fujian, who had migrated to the river port during the Huguang tian Sichuan migration period. Credit: DFAT

References

Sichuan and Qing Migration Policy, Robert Entenmann

The Sichuan Frontier and Tibet, Yingcong Dai

Material from Huguang Guild Hall, Chongqing

Click here to return to the Australian Consul-General's Blog on Southwest China