Yunnan food: hidden cornucopia

2 July 2020

My first taste of Yunnan-style cooking was over a business lunch in Beijing, where I was working at the time. In contrast to northern style dumplings and noodles, Yunnan tastes were refreshingly different. Flavours and ingredients were exotic. They hail from China’s southwest corner, right next to Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam, from where the influences are unmistakeable.

To an Australian palate, the tastes were not unfamiliar. Spicy and sour dishes such as barbequed pork, spicy salads, and grilled fish with lemongrass, remind me of Thai dishes popular in Australia. I took an instant liking and declared Yunnan food among my favorites.

So imagine my bewilderment when I visited Kunming, Yunnan’s provincial capital for the first time in 2017 and found that the food there was nothing like my favourite dishes in Beijing. Why was that?

I eventually understood that the reason lies in the sheer diversity of Yunnan food. The province has an enormous variety of plant life and microclimates, resulting in a multitude of food options. The large numbers of ethnic groups in the province adds further variety to cooking methods and traditions.

Whether you’re a businessperson, student or tourist going to Yunnan, it helps to know what to expect, especially when Yunnan cuisine isn’t well-known in Australia. You’d delight your Yunnan hosts if you showed interest in their food. It’s a sure way to break the ice and strike a conversation. There is much to talk about in terms of Australia’s substantial links with Yunnan (see here and here).

Here are some essential things about Yunnan food.

Steamed chicken soup – a divine elixir

Steam-pot chicken (汽锅鸡qiguoji) is a famous Yunnan culinary specialty. This sublime dish is the ultimate essence of chicken soup.

Scented with wine, ginger, and spring onions, the soup is prepared in a special steam-pot, made out of terra-cotta with a chimney in the middle. Placed over boiling water, the steam pot cooks the chicken by means of the piping steam and juices of the ingredients. As the steam condensates, a rich and aromatic elixir is created. The soup never boils.

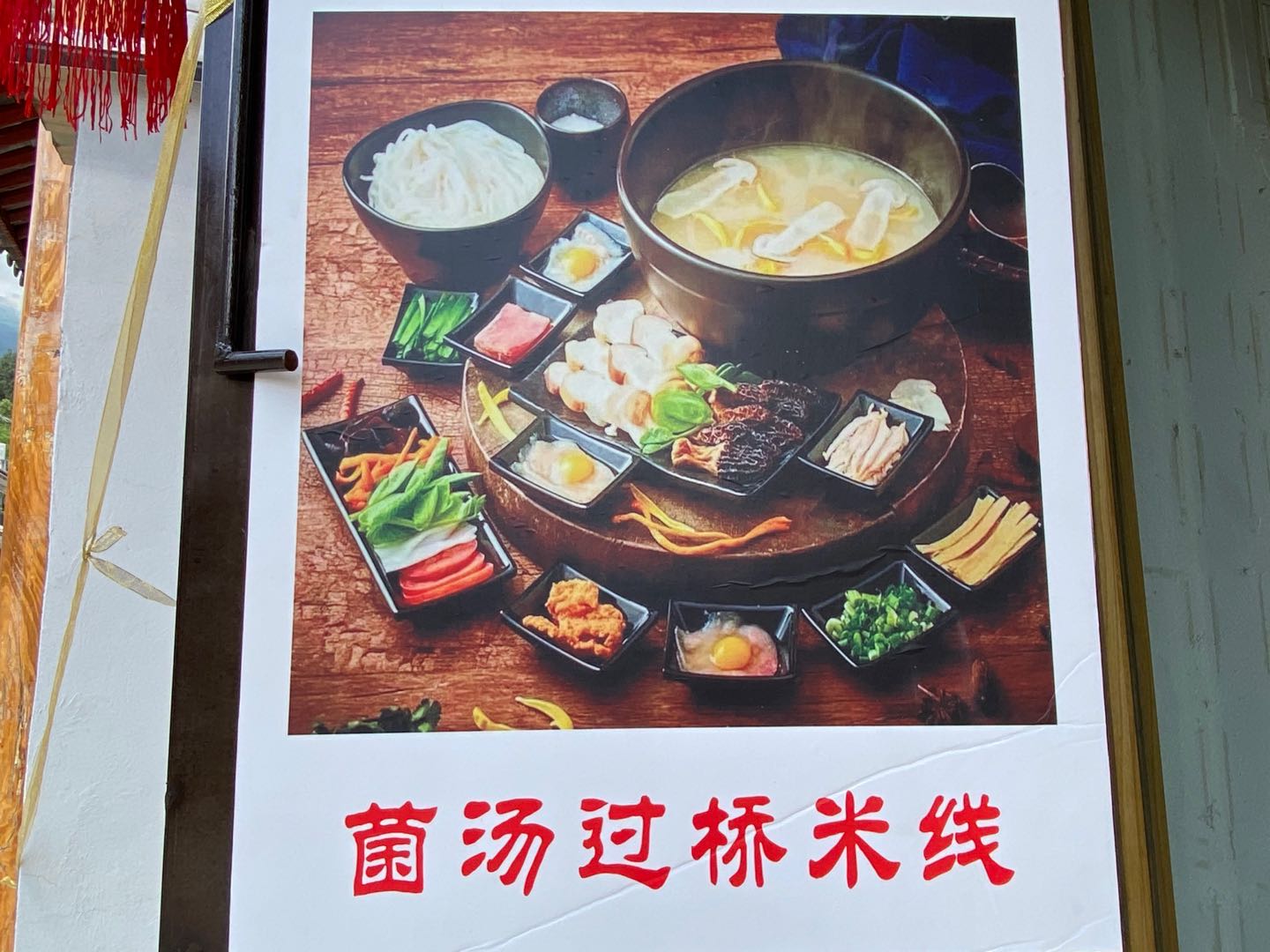

Bridging divides through the best noodle soup

Crossing the bridge noodles come with a delightful backstory. Credit: DFAT

Another Yunnan classic, “crossing the bridge noodles” (过桥米线) is nourishing and comforting. It may just look a large bowl of rice noodles, with hot broth, meat and vegetables, all in separate bowls. But it is much more – the soup is made with chicken, pork bone and seasonings, such as star anise and ginger. Distinctively, a layer of chicken fat is ladled on top of the soup to insulate it and therefore keep it warm longer.

Legend has it that the dish was invented by a woman whose husband was on an island studying for the imperial civil service examinations. Each day, she would bring him food, but by the time she had crossed the bridge, the soup in the earthen pot would be cold and the noodles soggy. Her solution was to put a layer of oil on top of the hot broth to keep it warm. The noodles and other ingredients were kept separately. When she arrived, she mixed the two containers together for a warm soup.

To really impress your Yunnan hosts (or annoy them), you could say that historians haven’t been able to ascertain the identities of the couple, nor the bridge from where the dish famously came from. The story could be an early marketing ploy. Some historians say the name comes from the way the ingredients are transferred between bowls. The process is similar to crossing a bridge between bowls, and hence it is called "crossing the bridge" noodles.

Ham and cheese – the familiar and the exotic

While cured pork can be found elsewhere in China, Yunnan’s variety of hams is unique. Hanging from beams of houses in villages are whole hind legs of ham, something you expect in Spain. Yunnan ham is an important ingredient in many local dishes, adding umami and depth of flavour. A famous chef suggested that I add chopped Yunnan ham in my special bolognese sauce. This “secret” ingredient has left my Italian friends guessing and confused for years.

I have to say Yunnan cheese doesn’t do it for me but it’s worth a try, especially when no other region in China use it so frequently as part of their daily diet. Rushan (乳扇) or rubing (乳饼) is made from freshly made cows' milk curds, which are pulled and stretched into thin sheets, wrapped around long bamboo sticks and hung up until yellow and leather dry. It is then deep fried and sprinkled with sugar before eating.

Yunnan specialties: Er Kuai pancakes (left) and Rushan cheese (right). Credit: DFAT

Er Kuai pancakes. Credit: DFAT

Mushroom heaven

If you like mushrooms, Yunnan has more than 200 edible species. They come from remote mountain forests with their own microclimates that nurture their growth. You’ll find mushrooms starring in various dishes in Yunnan – they’re definitely worth trying. If you want to be immersed in Yunnan mushrooms’ umami goodness, mushroom hotpot is the way to go.

Mushroom BBQ skewers. Credit: DFAT

If you come in summer and autumn, you’ll have fresh wild mushrooms to enjoy, such as the highly sought after (and expensive) matsutake (松茸). Otherwise, the dried varieties are also plentiful and excellent.

Dipping sauces galore

I am told that a Yunnan dining table without dipping sauces has no soul. So each dish comes with its own sauce or even several dipping options. Depending on the dish, there are dry dips made of any combination of dried chilli powder and other condiments; chilli oil infused with a variety of herbs, endless varieties of chilli sauces; pickled vegetable chutneys; tomato-based salsas; raw mince beef dip; braised fermented meat dip; roasted pickled dips; and many more that challenges my vocabulary and taste buds.

Regional differences rule

Food of the Dai people in southwestern Yunnan is typically sour, spicy and has less oil. Fresh herbs, including lemongrass, are used liberally. Insects are a part of the Dai diet. The ethnic group is related to the Thai people.

Tibetans live in the high mountains of northwestern Yunnan. Yak meat, which comes grilled, preserved or freshly sliced for stir-fries and hot pots, feature prominently.

The local Lijiang speciality among the Naxi people is the blood sausage. Made from pig’s blood, rice and herbs and encased in pork intestine, it is fried or steamed. A thick, soft bread, called baba (粑粑) is popular local street food. It is served either plain or with minced pork, corn or red bean.

Around the Lake Erhai area near Dali, the Bai ethnic group makes a stewed carp casserole that is packed with spicy flavours. Found on every family table is er kuai (饵块), compressed rice cakes that are sliced, then added to meat and vegetable dishes.

In other regions, the central part of Yunnan around Kunming has flavours that are sweet and salty, while the southeastern part of Yunnan is known for its fermented tofu. Northeastern Yunnan has a variety of hams as well as spicy influences from Sichuan.

Must try

Yunnan cuisine isn’t represented by one specific flavour. It is a cornucopia of cooking styles that reflect the province’s rich biodiversity, different ethnic traditions, and influences from neighbouring regions. As such, it is among the most exciting and unexpected of all Chinese cuisines.

Click here to return to the Australian Consul-General's Blog on Southwest China